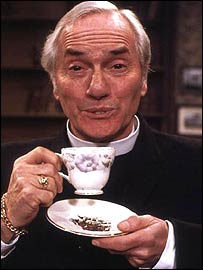

A Rector knows his place - between a rock and a hard place

Greetings and thanks

You have worked hard on the Rectory and the garden. One of you only narrowly escaped amputation of a foot—an act that takes selflessness to new levels. The garden, greenhouse, new path, patio and fence look very good. The Rectory—and please call in when you are passing—looks lovely. Painting all interior walls magnolia has worked a treat to give the place a sense of light and cheer. Our visitors from England were impressed by Portlaoise, Ballyfin and the Rock, and by your friendliness to them. The institution service was a real delight and great fun, and the refreshments afterwards were magnificent. It is dangerous to mention names, so I won’t—but thank you to wardens, musicians, flower arrangers, cleaners, bakers and caterers, bringers-up, readers, gardeners, craftsmen and craftswomen—we thank you all for your industry and welcome. You could not have been more welcoming.

Moving is exhausting

Moving to Ireland the second time is easier than the first in 1988: not only familiarity, but also this time no house-hunting or worries about schools for children etc. However, we are 23 years older. On Irish TV when we arrived is Rose of Tralee, which was on when we first came house hunting in 1987. Some things never change.

Knowing me, knowing you. It will take time for me to get to know you, and you me. It will take a while for me to be able to put faces to names and names to faces. Please bear with me, and don’t be offended if you have to correct or remind me: no insult is intended. The poet T S Eliot wrote:

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make and end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from.

and:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

One of the messages of these two snippets is that through exploration we begin to know ourselves. We make decisions about ourselves partly on the basis of what we sense around us—the environment—and in order to do this we need to explore. We grow through exploration. The Church in Europe needs to interact more with the environment in which it finds itself. It needs to become involved with (engage with, though I dislike that management jargon) contemporary culture, with physics, with biology—with what it means to be human. If it does not, it will surely die. You might think it’s already dying. Maybe that’s a good thing since death precedes resurrection. Archbishop Michael Ramsey said ‘it may be the will of God that our Church should have its heart broken, and if that were to happen it wouldn’t mean that we were heading for the world’s misery but quite likely pointing the way to the deepest joy.’

It’s inevitable that there will be frustrations and friction as we step onwards, trying to adapt to the world as it is, rather than as it used to be or as we wish it could be. Our Lord’s ministry was always concerned with getting people to come to terms with the situation they were in, rather than the situation they wished they were in. That is what healing means—it is not about cure, but about acceptance. And that is a big part of salvation. Think about the word: save, salve, heal – all part of shalom, peace—and peace does not mean suppressing anger, but rather is a process in which the causes of anger are exposed so that they can be addressed. If you have a festering abscess, sticking an elastoplast on it is useless. You need to open it and clean out the pus. Christianity is not about being nice. I hope no one will ever call me nice. (No one yet has. I’ll know you’re trying to insult me if you do.) Irritations and robust discussion are the grit around which real pearls may form. The pearl we seek is eternal life—nothing to do with life after death, but everything to do with life here and now. Quality of life, not quantity. Eternal, out of time, in the present. Instant by instant. ‘Thy kingdom come on earth as it is in heaven’ is about state of mind. It’s about how we see ourselves. I’m certain that Christians on the whole do not spend enough time looking into themselves: get yourself straightened out first, like on the aeroplane where you are exhorted in an emergency to put your own mask on before bothering about anyone else’s. A man that looks on glass [mirror], on it may stay his eye, or, if he pleaseth, through it pass, and then the heavens espy. For too long church people have been concerned about telling others what to do, rather than looking into their own innards.

So what is the point of being a Christian? For me, it is this: I came that all may have life and have it in abundance. And: that all may have power to become sons and daughters of God. We do this by letting go of attachments. If you want to know more, come to church.

Things you need to know

My right ear hears better than my left. I do not find hearing aids much use because they magnify all the background. It is often an advantage to be hard of hearing, especially at meetings. Susan wears her hearing aid more often than I wear mine. Vision in my left eye is restricted (retinal detachment in 2006). I like tea strong, with milk in second. Please sing loud: enthusiasm is more important than accuracy. Please say the spoken parts of the service with enthusiasm. If you don’t we will repeat them until I think they are loud enough (seen the film Groundhog Day?). Whatever we do in church says something about our humanity so let it be with verve. Let go of inhibitions. To be fully human is to approach the divine. Let delight be our watchword: desire and delight, prayer and parties. Remember this: without joy and delight, we are in hell. That indeed was St Isaac’s definition of hell.