A paper for the meeting of the British Association of Clinical Anatomists at the Burton on Trent meeting, 14 December 2017

A paper for the meeting of the British Association of Clinical Anatomists at the Burton on Trent meeting, 14 December 2017

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was the Anatomical Society and the Journal of Anatomy. They were in the beginning with God, and without them was not anything done in anatomy that was done. And the Professors of Anatomy saw themselves as the Lord Almighty. They terrorise and pulverise. They march through the breadth of the earth to possess the dwelling places that are not theirs. They are terrible and dreadful, their judgment and their dignity proceed from themselves. And lo, it came to pass that the people rebelled inwardly in their hearts. They cried to the Lord “wilt not thou deliver us from these bitter and hasty foes?” And the Lord raised up prophets, Coupland of Nottingham and Scothorne of Glasgow. And through them the Lord came to the aid of the oppressed. And lo! BACA was born.

It’s fun to see the formation of BACA in these Biblical terms, and it is not inaccurate. But there’s a bigger story to tell, and since this year marks BACA’s fortieth birthday, I shall do so. Of course, I’m not an historian, but I’m one of the few people alive who witnessed BACA’s birth in 1977 just along the corridor from my office in Nottingham. My recollections are thus first-hand and are as reliable as memory ever is.

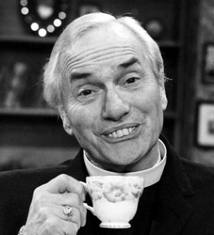

First, a brief autobiographical sketch. I was at Cambridge for preclinical studies and then King’s College Hospital in London for clinical training and preregistration house jobs, as they were then known. I went to Nottingham as anatomy demonstrator in 1976 then Lecturer in 1977. In 1988 I began as Professor of Anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, in Dublin—a medical school as well as a postgraduate college—and then in 2003 was appointed to Nottingham’s Graduate Entry Medical School at Derby. In 2006 I was ordained into the Church of England, becoming Vicar of Burton in 2014.

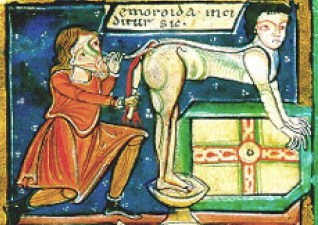

The origins of BACA are intertwined with two main medicopolitical trends: first, the decline of anatomy as a discipline in the medical curriculum, and second, the loss of medical graduates from departments where they had been predominant. I know that I am talking today to a mixture of scientists, physios and medics, and I apologize if what follows seems irrelevant to many of you, but it is important in the embryonic development of the society, so bear with me.

The decline of Anatomy

I enjoyed undergraduate anatomy. I was riveted by the first lecture in October 1969 concerning lemurs and lorises and thumbs, part of a series on the evolution of Man. Subsequent anatomy memories centre on Max Bull, the doyen of Cambridge anatomy teachers, who gave us a definition of anatomy that has stayed with me: “the study of the structure and function of the growing and changing living organism, not necessarily human”. It’s not elegant but, like a thong, it covers the essentials, especially, as Max was at pains to emphasize, the growing and changing bit.

I was fortunate in the Cambridge anatomists of that time, who with one exception were affable, approachable and interested in students. So when during clinical years I realised that practising medicine was not for me, I thought that if being an anatomist involved what Max Bull did—welfare and nurturing of students using the vehicle of a subject that interested me—then an anatomist is what I would be.

In the third clinical year I approached several professors of anatomy about a job, and ended up in Nottingham because it was a lovely day when I visited and Rex Coupland, the professor, was charismatic. It was a good decision. I immediately saw the value of the brand new systems-based course that resulted in anatomy being significantly trimmed down, with much less time spent on dissection.

Listening to colleagues who had done time at other places, I realized how fortunate I’d been in Cambridge. I heard that more than a few Professors of Anatomy elsewhere were belligerent and irrational, and bullied their juniors and students. I witnessed it in external examiners

This is relevant to the decline of anatomy. In the 1970s and 80s, all the influential people in medical schools had had to endure hours wasted on dissection, all had been made to learn anatomy in excessive detail, and a fair few had suffered from the bad behaviour of some anatomists. Not surprisingly, they resented anatomy and they resented some anatomists. They were determined to cut anatomy down to size. They were abetted by the new discipline of Medical Education, then on the march, many of whose enthusiasts stated openly that doctors no longer needed to have facts at their fingertips. There was growing opposition to what they, wrongly, called didactic teaching

Things did not get better. The systems-based curriculum developed in many places in a way that may have suited metabolic processes but all but wiped out regional anatomy. The understanding of human biology as a product of evolution and adaptation, as imprinted upon me by Max Bull, sank without trace. I must be one of the last medical students to have enjoyed a term studying serial sections of pig embryos as part of an undergraduate course.

What was to be done?

With their clinical training and their clinical eyes—Coupland had begun to train in neurosurgery—BACA’s founding fathers were certain that only medically qualified staff were capable of teaching clinical anatomy. But there were hardly any left. So the question for them, given the image problem and the brain drain, was: how can we in anatomy recruit and retain medics?

The answer, they thought, was twofold: money and status. Rex told me that he saw BACA as a trade union that would lobby for preclinical medics to be paid more. Furthermore, the founders saw it a means of having medical anatomy recognized as akin to a clinical specialty. The trouble was that Rex and Ray didn’t know how to achieve these aims—indeed, given that they were both adept medical politicians in university life, they displayed surprising naivety.

First, money. Formerly, medics in preclinical departments had been paid more than non-medics doing the same job, but this differential had been abolished some years back. No salary committee in its right mind would reverse that decision for the sake of a miniscule number of peculiar medics. Perhaps the founders were thinking in terms of a salary enhancement, for Rex was the recipient of a hefty NHS merit award for which he attended at most one ward round a week. If he thought that that arrangement would catch on with NHS administrators, he must have seen pigs with wings. As for payment for clinical duties undertaken by anatomy staff, of which I was for over a decade a beneficiary, the resentment created by my not being available for university duties for one session a week was considerable. That wouldn’t have survived in the increasingly regulated NHS.

Second, status. I’m afraid Rex and Ray were living in cloud cuckoo land in imagining that clinicians would support any proposal to give senior anatomists clinical privileges. Unless the definition of clinical was twisted to mean what it patently does not, anatomists could never be clinical. At that time I became a member of the BMA Medical Academic Staff Committee, and believe me I know just how little support there was for such an idea. The clinicians simply laughed. In any case, Rex and Ray were wrong. Neither money nor status would have dealt with the image problem. Medics in anatomy were in many cases rightly considered maimed, unable to cope clinically, or, like me, deranged in turning their backs on clinical practice and salary.

It was all too late. King Canute couldn’t stop the waves, and neither could BACA.

Consequences

In the eyes of junior staff, BACA was compromised from the beginning. It was snobbishly hierarchical. For full membership you had to be a medic, and a senior anatomist to boot. Anything else meant a lesser category. And right at the bottom—sorry about this, all you scientists—were the ‘mere’ PhDs. The Association looked like an exclusive club for Rex’s and Ray’s friends and relations. My non-medic colleagues were outraged. The powers that be eventually relented, and this discrimination was abolished, though not soon enough. It left a bitter taste, and non-medic anatomists shunned BACA in favour of other scientific societies, leaving BACA meetings in the early days with little of great worth other than a good meal.

How did clinicians view BACA? I can only go by what I deduced from meetings. I should say that I was never a great meetings enthusiast. As a teacher I felt an impostor as scientist. As someone who did one ENT clinic a week, I felt an impostor as clinician. I was at home with students, provoking them to explore, to think, to imagine, to learn, and to ask questions, but to be on the receiving end of a comment from an eminent scientist which began “Dr Monkhouse, I listened to your paper and I have a question” was to render me incoherent in the sure and certain knowledge that evisceration was imminent. But to proceed. Many of the presentations at early BACA meetings came from only a handful of research groups—we’re back to the private club. Most surgeons looked elsewhere to flex their academic muscles, and few were enthusiasts for BACA or indeed anatomy. I was astonished to hear a Professor of Surgery tell me, the Professor of Anatomy, that he didn’t care what a structure was, or what it was called, or how it developed: all he cared about was whether or not he could cut it.

For these and other reasons, BACA was viewed by non-medical staff as elitist, and by clinicians as not really kosher. BACA meetings and the journal Clinical Anatomy came to be regarded by some in both camps as second or third best. It was fighting for its life as soon as it was born.

The future

I’ve been off the game for over a decade, so what value my comments have is for you to judge. However, as Max Bull remarked over 45 years ago, I have an analytical brain, added to which the view of the forest is better from the edge than from the middle.

The organization I work for at the moment is run by yesterday’s people making decisions for tomorrow without heeding the concerns of those that will have to bear the consequences. Is this true of BACA? Judging from your website, I think not, indeed I have the impression that you have worked hard to move on from those incestuous and hierarchical early days.

The future of an organization depends upon its capacity to be of service to others. So I suggest that you continue in that direction in the knowledge that you are on the right course. The future of BACA depends not on juniors tugging the forelock to grand old men, but on the extent to which those with experience can be useful to those trying to acquire it.

You rightly offer yourselves as a forum for gaining experience to anyone who wishes to explore clinical anatomy, no matter how tangentially. Find out what trainees need and work with them to provide it. Help them build their portfolios, and gain skills in presentation, writing and editing. Think back to when you were young and ask yourself what made you anxious. Help trainees to master these things.

Your committees will need to include more than a token trainee, so sling off the superannuated. If trainees are hard pressed to find time to serve, then organize things to suit them. I don’t want to get overly theological about this, but didn’t someone once say that the first would be last and the last first?

Many of the scientists among you will know more embryology than the medics. Teach them! It is hugely important in several clinical and scientific areas. How can anyone understand the function and layout of the cranial nerves except in terms of evolution and embryology? How can anyone understand how a weak voice might signal a mediastinal tumour except in terms of evolution and embryology? The medics among you can help nonclinical staff get to grips with some of the more obscure consequences of regional anatomy in terms of diagnosis and treatment. Work with the Anatomical Society—after all they are wealthy while you, I understand, are merely comfortable.

Is there anything to be gained by working with the Royal Colleges in training programmes? I know it’s difficult to work with surgeons, especially those who are big in the Royal Colleges, for as with Yorkshiremen, you can’t tell them anything: they are multitalented and omniscient. But there are other disciplines …

Another flight of fancy. Alternative medicine is on the up. See if you can cooperate with some of its more anatomical branches. I was in terrible trouble early in my Dublin days for having conversations with osteopaths and physical therapists about how we could help with their training. My knuckles were well and truly rapped by protectionist surgeons. I still see nothing wrong with those conversations and remain unrepentant, especially since they had money to pay us. One of the things I learnt from osteopaths was the way in which neglected ideas from the past surface years later. For example, the gut brain, once sneered at, has a new lease of life. It was an osteopath that directed me to a book entitled “The Autonomic Nervous System” by Albert Kuntz, published in 1929. There are some prescient nuggets in there that might repay imaginative thought.

Now there’s a word: imaginative. Imagine how you could serve. Imagine how things might develop and plan for them. Maybe that’s the best advice anyone could give the Association as it looks towards the next forty years. You’ve done well to come from a precarious postnatal period to the state you’re in now, so keep your eyes open and your antennae alert and let your imaginations flower. You can be proud of yourselves.

Finally

When I saw that BACA was coming to Burton, my first thought was “perhaps they’ll give an honorary member, or whatever I am, a free dinner”. And so you did, last night. It pays to be cheeky: “ask and you shall receive” is a phrase I read somewhere. It’s lovely to meet you, to renew friendships, and a real pleasure to begin to get to know Neil Ashwood. When we first met he asked me if I knew any connexions between Burton and Anatomy to which he could refer in his speech. I said modestly “not really, only me.”

Friends, thank you for your invitation, for feeding me, and for listening to me.

North Korea has long fascinated me.

North Korea has long fascinated me. The 2018 summer organ concerts at St Modwen’s finished last Wednesday. We went out with a bang.

The 2018 summer organ concerts at St Modwen’s finished last Wednesday. We went out with a bang.

A paper for the meeting of the British Association of Clinical Anatomists at the Burton on Trent meeting, 14 December 2017

A paper for the meeting of the British Association of Clinical Anatomists at the Burton on Trent meeting, 14 December 2017 A recent report from the C of E tells us that cathedrals are “amazing” places doing awesome things. Leaving aside the inflation of language that I so deplore, it occurs to me to wonder how well ordinary churches would do if they had access to at least half the resources thrown at cathedrals.

A recent report from the C of E tells us that cathedrals are “amazing” places doing awesome things. Leaving aside the inflation of language that I so deplore, it occurs to me to wonder how well ordinary churches would do if they had access to at least half the resources thrown at cathedrals. SWMBO draws my attention to an article in yesterday’s Church Times (13 October 2017) that explores the effects of clergy stress on clergy spouses.

SWMBO draws my attention to an article in yesterday’s Church Times (13 October 2017) that explores the effects of clergy stress on clergy spouses.